Reflections of an eyewitness

Sierra Leone Telegraph: 20 December 2014

“Operation Octopus”, “Operation Barras”, “Operation Final Push”. These were some of the code names for specific military assaults against the Revolutionary United Front during Sierra Leone’s civil war.

“Operation Octopus”, “Operation Barras”, “Operation Final Push”. These were some of the code names for specific military assaults against the Revolutionary United Front during Sierra Leone’s civil war.

Not to be undone in ‘operational expressions’, the rebels also declared their own operations. We will not forget that infamous macabre “Operation No living Thing.”

Over a decade after that civil war, we are witnessing the deployment of special operations for a different kind of war: the professed war against the invisible, but arguably a more lethal enemy – the Ebola Virus Disease.

In September, the government of Sierra Leone declared “Operation Ose to Ose Ebola Talk”. And on 17th December, 2014, President Koroma declared another operation – “Operation Western Area Surge”.

I have the feeling that like the rebels, this enemy has also declared its own operation – “Operation Upset Everyone”.

Meanwhile, ahead of the festivities, health authorities and government continually remind Sierra Leoneans of the Public State of Emergency and its implications for the public.

But the death of Dr. Victor Willoughby (Photo: Centre), one of Sierra Leone’s “medical colossus” in the morning of 18th December, 2014, has caused anguish among many people in the Western Area and abroad.

But the death of Dr. Victor Willoughby (Photo: Centre), one of Sierra Leone’s “medical colossus” in the morning of 18th December, 2014, has caused anguish among many people in the Western Area and abroad.

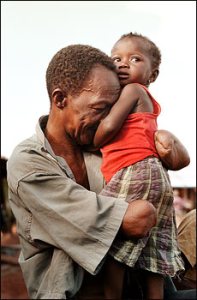

Like the rebel war, the Ebola incursion has not only inflicted economic hardship upon Sierra Leoneans, it has also killed many of them and taken the ‘life’ out of the survivors, by making it hard for them to reintegrate into their communities.

This is also a metaphorical throwback to the civil war years, when people who had been held hostage by the rebels, found it similarly difficult to be accepted back into broader society.

Indeed, this epidemic bears some of the hallmarks of the civil war. President Koroma calls it “a war with a vicious enemy”. Their similarities abound.

Like the rebel war, the initial local response to the outbreak was bungled and lackadaisical.

Also, the world community initially regarded the outbreak as Sierra Leone’s problem and looked on, while the country-side was ravaged. International action and even national consciousness were only aroused, when the horror and brutality of the virus besieged the cities and wreaked even more agony.

Eventually, and like the war, the world responded and now everyone else is here; the Nigerians, Chinese, the Americans, the Cubans, the Italians.

The British too are here with a war ship, man and machine. They are building treatment and holding centers.

The United Nations is also here as UNMEER in the place of UNOMSIL and its war paraphernalia.

But like the rebel war, the mandate was as inadequate as was the initial response.

Lack of proper coordination, international politics, anxiety and fear competed with reasoning in driving the actions. Thankfully, things are looking better now.

The trouble is, like the war, before Foday Sankoh attacked in 1991, the military was already in a bad state of preparedness. In this – Ebola war, the health sector was already under-resourced, especially regarding the number of specialists working in public health facilities.

According to the Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS), there were only 72 Registered Nurses, 47 Public Health Nurses, 12 Ophthalmic Nurses, 56 Nurse Anesthetists and 206 Community Health Nurses for a population of about 6,000,000.

Human resource constraint was not the only ailment of the sector. Poor conditions of service continue to afflict the sector.

The sector also faced serious logistical challenges. For example, there were only 50 ambulances, 24 secondary hospitals and 9 referral hospitals (sic).

Critical equipment such as dialysis machines and other diagnostic equipment were almost non-existent.

The few laboratories that existed were either poorly manned or poorly equipped. Certainly, there was only one laboratory capable of testing for Ebola. The list goes on and on; and although a whole directorate existed, structures for disease surveillance, prevention and control operated only on paper.

And, like the rebel war, corruption has also reared its ugly head. There are concerns raised in many quarters that monies and other resources meant to keep the enemy at bay are reportedly being mismanaged, misappropriated and brazenly diverted to personal use.

The Chief Executive Officer of the National Ebola Response Center recently complained about sleaze hampering the fight to defeat the epidemic.

There is also the public weariness and impatience, understandably so, adding to the overall confusion. Just as they did during the war, the panic-stricken masses are running away from the brutal enemy, sometimes in the dark of night and early hours of the morning.

As it was during the rebels’ advance, this nocturnal movement of suspected infected people is providing cover for the virus to spread across the country.

Not surprising therefore, when this virulent disease broke out, it was like the rebel war; the health workers were ill-prepared, ill-trained, ill-equipped and ill-motivated.

Like the war, even though the disease started in the remote parts of Kailahun, in the eastern part of the country, it literally marched on all the way to the cities – including the capital Freetown.

Like the war, even though the disease started in the remote parts of Kailahun, in the eastern part of the country, it literally marched on all the way to the cities – including the capital Freetown.

During the war, soldiers dropped their outdated weapons and abdicated their positions. In the face of the Ebola onslaught, while many are resisting and bravely confronting this lethal invisible enemy, some of the health workers have had cause to abandon their posts.

Ebola has invaded Sierra Leone, successfully targeting health workers, particularly nurses and doctors.

Nearly 200 of them have died. The nurses have borne the brunt of this attack, with over 130 of them having so far lost their lives. Many of the surviving health workers are now watching over their shoulders.

Nurses are very worried for many reasons. The high death toll is demoralizing, especially with the belief that once infected, it is almost certain that they would die. This perception is striking fear even in the bravest among them.

Nurses are possibly more exposed to the virus than other health workers. Before a doctor sees a patient, several nurses would have carried out preliminary assessments. After the doctor would have seen the patient, it is the nurses again that would administer treatment and give care.

But the calamity that has befallen the nurses has been muffled in the uproar over the rising loss of the doctors.

The nurses’ demise is simply reported as a statistic. They are the country’s unsung heroes and heroines. The sad reality is that many have figured out that it is better to stay alive than to become an unsung hero.

The consequence could be that, rather than going the extra mile to save life, they may be choosing the option of taking extra caution.

For the doctors, the history is as woeful as the current situation is devastating. Figures from the ministry of health show that there were only 3 physicians, 1 pathologist, 4 surgeon specialists, 3 obstetricians/gynecologists and 2 pediatricians in the public service.

Below is a list of the doctors that have so far succumbed to the virus. The majority of these 11 highly qualified fallen heroes and heroines were from the public health service.

Below is a list of the doctors that have so far succumbed to the virus. The majority of these 11 highly qualified fallen heroes and heroines were from the public health service.

* DR. VICTOR WILLOUGHBY – Died 18th December 2014

* DR. SOLOMON AIAH KONOYEIMA – Died 6th December 2014

* DR. THOMAS T. ROGERS – Died 5th December 2014

* DR. DAUDA KOROMA – Died 5th December 2014

* DR. MICHAEL KARGBO – Died 18th November 2014

* DR. MARTIN MAADA SALIA – Died 17th November 2014

* DR. GODFREY GEORGE – Died 3rd November 2014

* DR. OLIVETTE BUCK – Died 14th September 2014

* DR. SAHR J. ROGERS – Died 27th or 30th August 2014

* DR. MODUPEH COLE – Died 13th August 2014

* DR. SHEIKH UMAR KHAN – Died 29th July 2014

May their souls rest in peace.

It is estimated that it takes an average of 15 years in the UK and US to train one specialist doctor.

Now all of these have gone in just a few months – some within a few hours of each other’s passing. Three of them – Dr. Salia, Dr. Konoyimah and Dr. Kargbo, died within 48 hours.

This brutality inflicted upon Sierra Leone’s “already compromised health sector”, suggests that effort at strengthening the human resource of the health care service delivery system has been reversed several decades.

The Free Health Care Initiative was introduced, salaries of health workers increased. Through the World Bank funded Reproductive and Child Health Project, incentives are provided for the satisfactory delivery of certain key services. The project also makes provision for essential drugs, running water, electricity, delivery beds and accessories and basic laboratory materials.

Like the rebel war, the collateral and direct damage of this devastation in Sierra Leone could only be determined after the Ebola war would have been won.

But for this victory to be achieved and soon, Sierra Leone needs more than just an attitude change. Sierra Leone needs a complete change of mindset in public, private and ordinary life of its people – it is everybody’s call.

Be the first to comment